Why Yield Curve Inversions Can Be a Key Indicator

The following is an update to an article we authored in October 2019, just a few months before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, many in the financial media have revisited the subject of inverted yield curves now that the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates for the first time since 2018.

As the term “yield curve inversion” has returned to the news, you may be wondering exactly what this is, what it portends, and why it’s getting so much press.

What is a yield curve inversion?

If someone borrows money from you, the length of time until they pay you back should be a determinate of how much interest you charge. The longer it will take until you’re paid back, the higher interest you charge, because the risk you bear as the lender is greater. For example, a 30-year mortgage has a higher interest rate than a 15-year mortgage. That’s common sense, right?

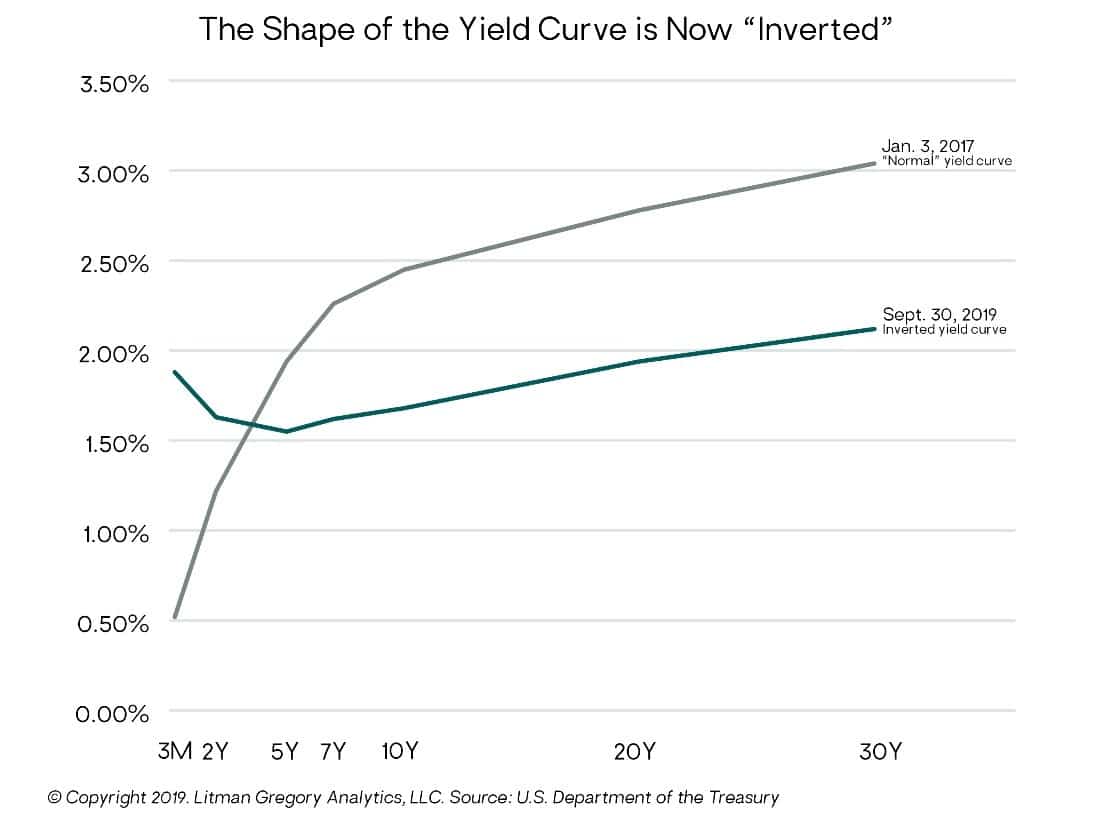

But in bond markets, this yield-time relationship does not always hold true. There are rare times when long-maturity bonds sport interest rates that are lower than short-term interest rates—yields are then said to be inverted.

What does this mean for investors?

In simplified terms, when short-term rates are higher than long-term rates, the market is saying: “Good times are here … but bad times are coming.” Central banks typically raise interest rates to curb inflation as the economy strengthens but lower interest rates to stimulate business activity when the economy is struggling.

Consider the following: As we write this at the end of March, a 10-year Treasury note is yielding about 2.32%, while a 5-year Treasury note is yielding 2.42%. Generally, when discussing an inverted yield curve, most are referring to the 10-year and 2-year Treasury bonds. The 2-year and the 10-year government bonds have bounced between a slight inversion, and an equal yield over the last several trading sessions.

Assuming investors have a long-term time horizon, what would make them buy the lower-yielding, more volatile long-term bond, rather than just rolling over a series of two-year bonds at the same rate or five-year bonds offering a higher rate?

Choosing the 10-year note makes sense if an investor thinks interest rates will fall enough over the next 10 years that locking in a 2.32% long-term return would produce at least

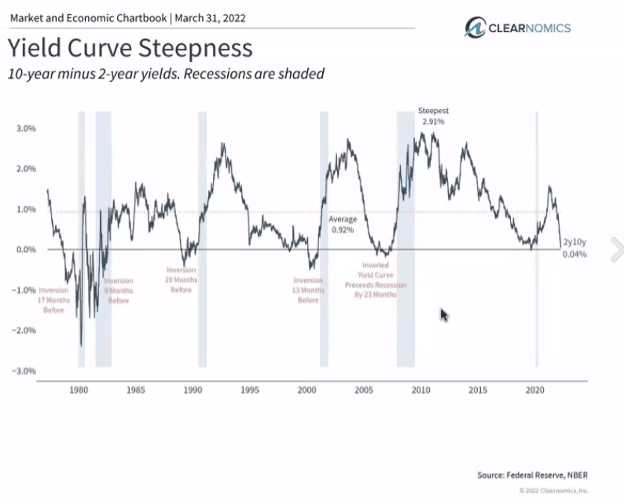

as good a result as a series of short-term bonds. Typically, some kind of recessionary event would be necessary to cause short-term rates to decline. Indeed, an inverted yield curve has preceded the last seven U.S. recessions. This is why many investors are concerned.

It’s important to remember, however, that the yield curve reflects investors’ expectations for interest rates, inflation, and economic growth. Investors are human after all; there is no guarantee that the market’s collective prediction will come to pass. A recession did not follow the yield curve inversion in 1966. The market experienced a recession after a brief inversion in late 2019, however, the global pandemic was the clear catalyst behind the slowing economy. One can certainly question the predictive nature of the last inverted yield curve, given how quickly the economy rebounded once restrictions were lifted.

Should we be Concerned a Recession is Imminent?

Many commentators have offered up plausible reasons why a yield curve inversion may not be indicating an imminent recession today:

- The unemployment rate is 3.6%. Consumer spending makes up 70% of the U.S. economy, therefore we currently lack a key component of a recessionary environment.

- Yields today are flat (equal across bond maturities) more so than inverted. A flat yield curve is not a recessionary signal.

- A yield curve can remain inverted for quite some time before a recession occurs. Temporary inversions have had limited predictive value.

- Fed Chairman Jerome Powell recently disputed the predictive nature of inverted intermediate-term rates. Powell suggested the Fed has research indicating the first 18 months of the yield curve (comparing 30, 60, 90-day rates, etc.) are more effective recessionary predictors. The 90-day treasury is yielding 0.72% vs 2.32% for the 10-year, far from an inversion.

Conclusion

Recessions are extremely difficult to predict. Typically, the economy is into a recession for multiple months before the consensus realizes and economists confirm. Investing certainly isn’t risk free, and one can always find a reason to be concerned about the economy and equity markets. Inflation and geopolitical unrest top the list today. The shape of the yield curve is worth watching; however, we think the shape of the yield curve (today) is not a reason to alter your long-term investment strategy.