Building an Optimal Retirement Tax Strategy

Investors often hear the phrase “don’t put all your eggs in one basket,” and interpret it as a warning against owning too much of one individual stock in a portfolio. In a broader sense, all investors, especially those in high income tax brackets, should also apply that caution to their future tax liability during retirement and consider the fundamental long-term strategy of tax diversification.

What is Tax Diversification?

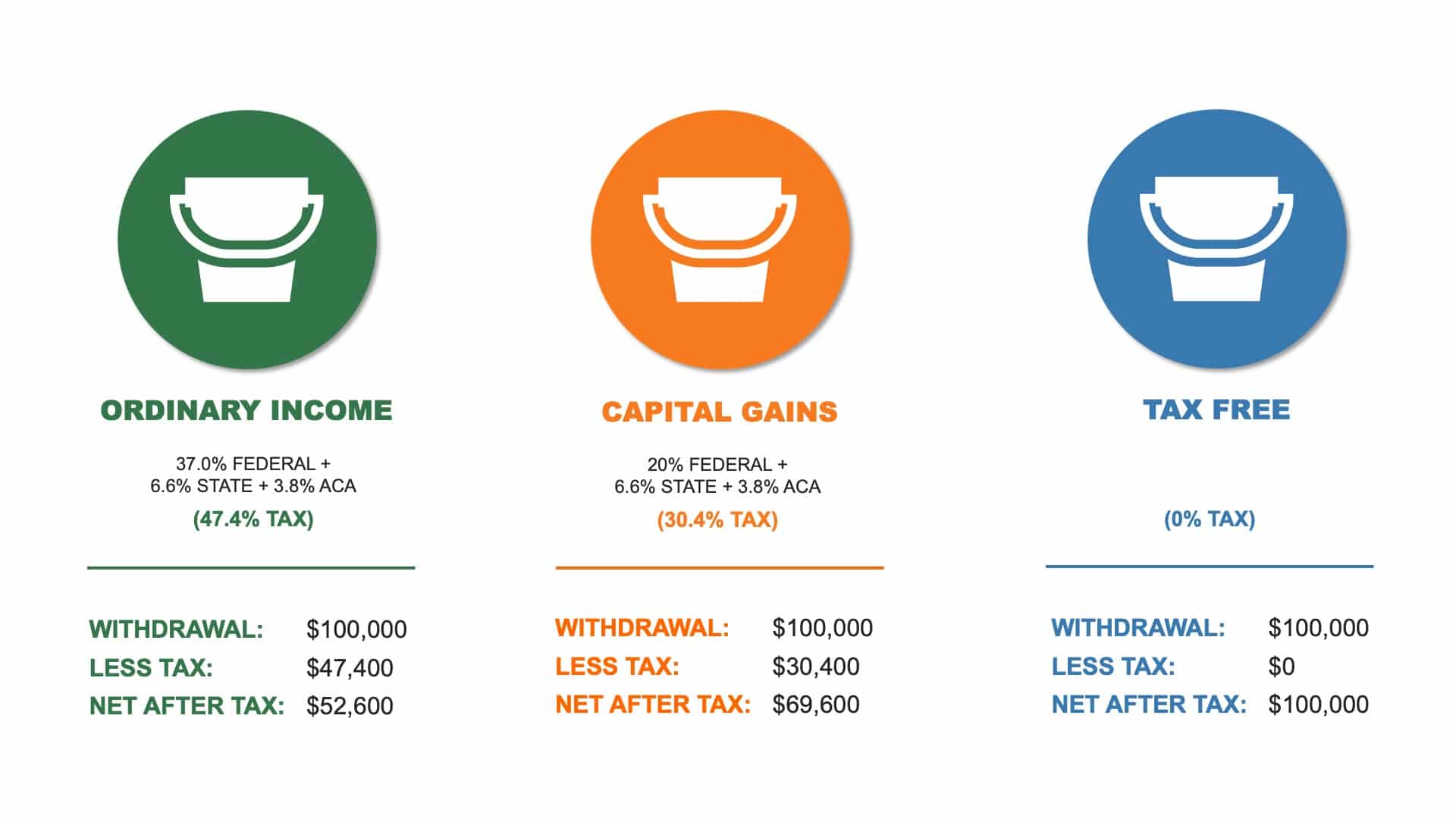

Tax diversification means building up wealth in three “buckets”: assets subject to ordinary income tax rates upon distribution in retirement, assets subject to capital gains tax rates, and assets not subject to any tax upon distribution. While many investors have heard of asset class diversification in the context of investing, it is also important to direct attention to diversifying your wealth according to tax rate exposure.

The illustration below may help you to visualize the value of having differently taxed “buckets” to draw from when you reach retirement. As the retirement/wealth distribution phase may last for many years, or even multiple decades, being diversified across three tax buckets puts you in a position of strength and gives you options for withdrawing income depending on the tax rates then in effect.

Assets in the first bucket include 401(k)s and IRAs where the contributions are made before taxes are withheld. During the distribution phase, these assets are taxed as ordinary income. Bucket #2 includes brokerage accounts and trusts where only the investment gains are taxed at capital gains rates. The third tax bucket incorporates after-tax assets, such as a Roth IRA or Roth 401(k). The money goes into these accounts after taxes are withheld and future distributions are tax free.

Many retirement savers gravitate toward the pre-tax bucket because of the tangible tax benefit. These contributions allow them to reduce taxes in a given tax year by deferring the tax liability on your retirement plan contribution. For high-income earners, this tends to make sense as they are at the upper end of the tax brackets. Opting to drive all of your savings to this bucket, however, provides little or no flexibility in future distribution years when your income needs are higher than the annual required minimum distribution (RMD), which is the amount of money that you are required by the IRS to withdraw from your retirement account(s) after reaching a specified age.

Spreading your wealth across the various tax buckets affords you greater flexibility in managing tax implications during the distribution years.

Building a Retirement Plan Withdrawal Strategy

Nearly all investors, no matter how seriously they take diversification, will have a significant balance in their QRP or rollover IRA when they reach retirement. As such, planning around when and how much to take out of these structures each year is important.

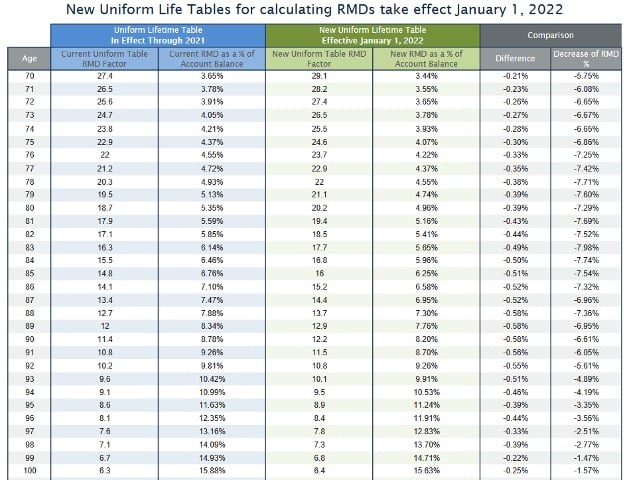

A new concept to explore in this area is focusing on the maximum amount that one can withdraw in a given tax year before being pushed into a higher tax bracket. This simply means taking the distributions before the actual required age. The biggest issue with waiting until age 72 (or older based on the recent passing of SECURE Act 2.0) is that you have no control over the actual amount you need to withdraw. You are at the mercy of life expectancy tables that the IRS establishes (see table below).

Source: https://www.fidelity.com/viewpoints/retirement/tax-savvy-withdrawals

In the table above, the green section “New RMD as a % of Account Balance”, displays just how large these distributions can get over time. By spreading out taxable income more evenly over retirement, you may also be able to potentially reduce the taxes you pay on Social Security benefits and the premiums you pay on Medicare.

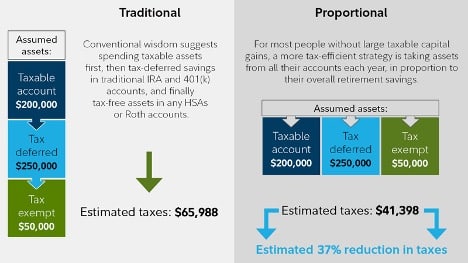

To further illustrate this concept, Fidelity compared the traditional approach to a more proportional withdrawal strategy with this hypothetical example1:

Joe is 62 and single. He has $200,000 in taxable accounts, $250,000 in traditional 401(k) accounts and IRAs, and $50,000 in a Roth IRA. He receives $25,000 per year in Social Security and has a total after-tax income need of $60,000 per year. Let’s assume a 5% annual return.

If Joe takes a traditional approach, withdrawing from one account at a time, starting with taxable, then traditional and finally Roth, his savings will last slightly more than 22 years and he will pay an estimated $66,000 in taxes throughout his retirement. Note that with the traditional approach, Joe hits an abrupt “tax bump” in year 8 where he pays over $5,000 in taxes for 11 years while paying nothing for the first 7 years and nothing when he starts to withdraw from his Roth account.

Now let’s consider the proportional approach. This strategy spreads out and dramatically reduces the tax impact, thereby extending the life of the portfolio from slightly more than 22 years to slightly more than 23 years. “This approach provides Joe an extra year of retirement income and costs him approximately $41,000 in taxes over the course of his retirement. That’s a reduction of almost 40% in total taxes paid on his income in retirement,” explains Lyalko.

Source: https://www.fidelity.com/viewpoints/retirement/tax-savvy-withdrawals

Long Term Planning Requires Flexibility

Regardless of the planning tools used to save for retirement or one’s distribution strategy, one of the fundamental pillars of any retirement plan should be flexibility. This can mean flexibility to withstand changes in tax rates, income needs, market performance, and personal health. A focus on tax diversification, as well as QRP withdrawal strategies, is one part of a holistic long-term plan.

1https://www.fidelity.com/viewpoints/retirement/tax-savvy-withdrawals